Minimalism

The Pursuit of Minimalism

Minimalism has come a long way. It recently got again a lot of traction with it’s highest search volume on Google ever recorded in January 2017. Because Minimalism is very hard to define, it leaves a lot of room for interpretation and its meaning shifted recently more from being a philosophy to being a lifestyle.

In his video Being a Minimalist the creator JP Sears jokes about the extremes of Minimalism. A lot of people moved to Minimalism out of different reasons: From being overwhelmed of capitalism and the accelerating speed of life, to caring about the ecosystem, as result of balancing sick excesses like fast-fashion and constantly rising consumption of resources, to people just following a trend to feel unique or setting a statement on their wealth, by not having stuff as a symbol of status.

The Spectrum of Minimalism

A lot of people misunderstand Minimalism as some form of a search for highly expensive design objects to fill their houses with, which is not Minimalism but just a form of hyper-capitalism. It’s not inherently wrong to surf on sites with Minimalist items to buy or be inspired by simple design, as long as it doesn’t result in buying stuff to try to become a Minimalist.

On the other side of the spectrum, you can see the extreme Minimalists, living out of a box, owning 19 items, racing to be the most minimal Minimalists, sitting in empty rooms on the floor. And of course, you are only allowed to use white and some black colors for everything as an extreme Minimalist. This form of Minimalism is only suitable for a few people. It deters a lot of people to try out Minimalism. But it’s definitely helpful for being interviewed in media, selling your book, or being invited to conferences.

Real Minimalism is not glamorous, it’s humble and a result of deep mindful thinking. It is a mindset or philosophy, not a method. And the reduction of physical possessions is often a result of Minimalism, not Minimalism itself, as Colin Wright explains in his article Minimalism Explained.

Criticism of Minimalism

Critics of Minimalism describe it as cold, empty, without personality. People following Minimalism would deny their past or prove their inability to connect to other people. It would be a hopeless attempt to control life, as Linda Tutmann described Minimalism in her ZEIT article Alles mein.

This misconception of Minimalism is the result of its shift to a lifestyle and of extreme Minimalist, who live in sterile homes. Minimalism is not about having as few as possible, but about not having stuff, which doesn’t bring joy or getting rid of stuff, which was acquired as a result of other reasons than a real need or love for an object.

The wrong reasons might be diverse: Boredom, inner emptiness, the desire of status, procrastination, the uncomfortable feeling of thinking of oneself, the attempt of freezing time for nostalgic reasons, and many more.

The Origins of Minimalism and Simplicity

As everything in this world is connected, Minimalism has its roots in a lot of different schools of thinking. One very closely related is Simplicity. I found this definition (source unknown) about the difference between Simplicity and Minimalism:

Minimalism is the reduction of quantity.

Simplicity is the reduction of complexity.

As Minimalism is also defined as Simple Living, Simplicity will inevitably be part of a Minimalist’s life. The reason is deep thinking often results in love for simple forms. Objects, which are resistant against temporary fashion, which endure times and follow the concept of form follows function.

As Kenya Hara writes in Wa: The Essence of Japanese Design, the origin of Simplicity can be found in the European modernism as a result of the society getting free of sole rulers (who were defined by objects of decoration and excess of material objects). Rationality was the basis of this concept, resulting in Bauhaus in 1909 or the founding of Domus in 1928.

The Japanese Simplicity is described as Emptiness by Kenya Hara and has a complex background: Japan was positioned at the end of many routes of cultural influence. From Rome along the Silk Road to Central Asia, China, Korea, and south from Turkey over India, South Asia, and north along with Russia. But after a civil war from 1467-1477 (ōnin no ran), which resulted in the destruction of a lot of objects of art (temples, statues, paintings, kimonos, etc.), may be out of necessity, a new form of simple and quiet design emerged.

Different ideas like shintō, zen Buddhism, and Daoism influenced this form of Simplicity (and Minimalism) in every aspect of life. In shintō the concept of emptiness is the result of the creation of a space for the kami (deities) to fill it. Zen Buddhism brought aspects like Upādāna (sanskr. the attachment, clinging, or grasping on ephemeral things). As a result many new ideas based on Emptiness, Simplicity and Minimalism emerged: wabi-sabi, kintsugi, japanese gardens, bonsai, ikebana, chadō or haiku.

Why to become a Minimalist?

Minimalism in its core idea should free a person from a lot of limiting things: Less stuff, to think of, less to hang your heart on, less to clean, less to deal with every day, less lingering of the past (Nostalgia), less fear of losing things, less debt, less guild for buying useless things. Instead, one gains more time, more space for people, more money, more inner peace, more space for thinking. Time for your health, relationships, passions, growth, and contributions.

That’s why I think extreme forms of Minimalism can easily result in less freedom. If a Minimalist owns only five shirts and needs to clean them every weekend or will run out of clean shirts, Minimalism hinders freedom.

My history as a Minimalist

I think I was always a Minimalist, even when the term didn’t exist. My first contact with the idea was in high school, where we had to read To Have or to Be? by Erich Fromm.

The next thing which influenced me was surely the book and movie Fight Club. It’s filled with quotes against consumerism, capitalism, and property. It has a lot of anarchic ideas, which is probably the main reason it was rated PG 18.

The things you own end up owning you.

The next step was probably reading David Allen’s book Gettings Things Done (GTD), which is a productivity system, but at it’s beginning is some inventory of your stuff. This way I got rid of a lot of stuff for the first time.

The exhibition LEVEL GREEN in Autostadt Wolfsburg introduced me first in a differently drastic way into the concept of sustainability. People could learn, by answering some questions about how they lived, how big their own impact on the earth was. To maintain my lifestyle from back then, it would need 1.8 planet Earth. This changed my idea of how to live responsibly a lot.

The books of Marie Kondō brought Minimalism again into my mind and I did another big cleanup of my flat. In general, Japan provides very often good ideas to the concept of Minimalism. This is because of their history (as mentioned above) and because Japanese homes are very small.

In the last years I changed my ideas of how to live in many ways:

On Getting Rid of Stuff

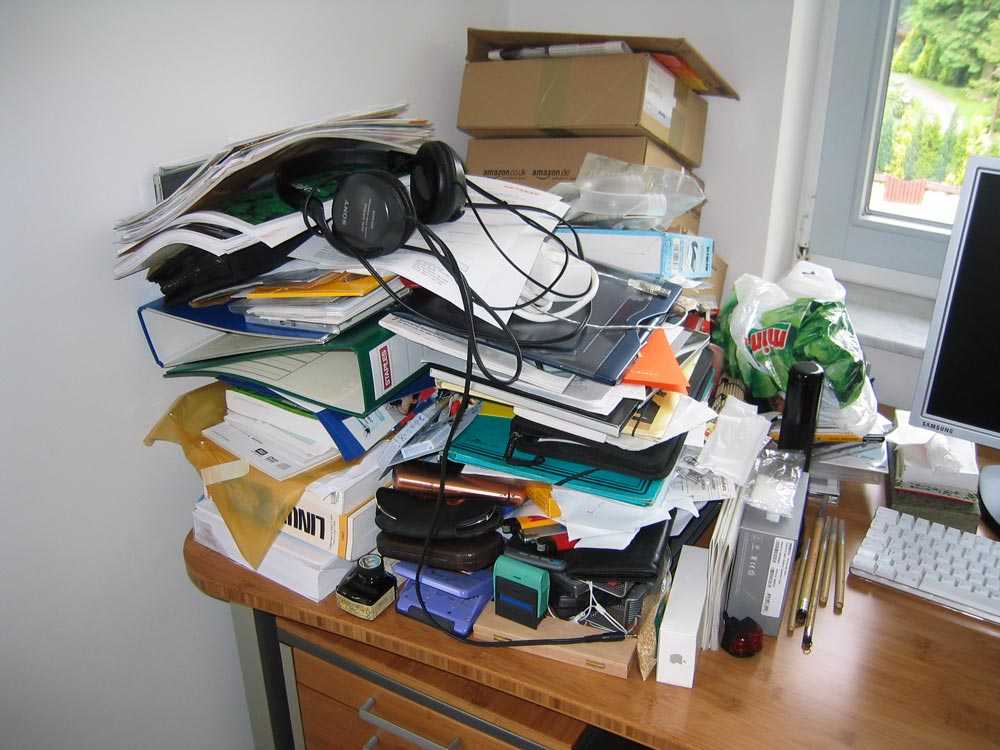

I cleaned my whole flat of things I didn’t like or needed any more. It took me three days to clean my basement from packages, cables, and technical waste, which I acquired over a period of 10 years.

I gave more than 150 books away (I still own 763) and sold my car. I use the subway, bus, car-sharing, and train to commute or travel.

I scanned most of my documents into digital form and recycled the paper.

Recently I counted all my possessions: I own 2486 items, which is a fourth of the amount a European person owns on average (10000 items). I counted everything, from my wardrobe to dental brushes. 356 items in my bedroom, 242 items in my corridor, 68 items in my bathroom, and 1820 items in my living room and kitchen.

On Consumption

I changed my relationship with consumption. Quality over quantity. I buy mostly natural things, made out of natural materials. I learned to find the passion for nice and crafty things (I bought a Traveler’s Notebook and a Laguiole en Aubrac knife). I try to buy fewer physical books, though I still love them. My rule for books is: They need to be designed with love and care or I’ll buy them as ebooks.

On Fashion

I never had a high interest in fashion, so this was easy for me. I buy mostly good quality; simple, plain, timeless. Black, white, blue, beige, and other simple colors. No motives or fancy slogans. Cotton, wool, leather, linen, denim. And I don’t care about the brand. But if the nicest and best fitting glasses have Dolce & Gabbana printed on the side, fine. I just try not to grab something just because it’s a special brand.

On Sustainability

I switched to green energy some years ago, to buy whenever possible organic food and think twice if I need some product. I still own no microwave or dishwasher and don’t miss them. I do waste separation (we Germans are world champions in this discipline). My waste disposal company wrote to me recently a letter, telling me I use little garbage (and waste money). I used only 305 liters of the yearly obligatory 1560 liter. Maybe I should think of reselling my waste rights.

On Living

When I was young I always wanted a big, big house (preferably on some remote private island). But living in a small space is quite helpful for a Minimalist. It forces you to make decisions in your own interest. I live on 51 m², and this is enough space for 1-2 people. That’s why I think twice if I really need to buy something. I like the concepts of small space living, but I’m happy to have a separate bedroom. This is much more relaxing, because of different temperatures in the living and sleeping area. And I do not keep electronics in my bedroom.

On Digital Minimalism

I deleted a lot of apps from my digital devices. Less distraction, fewer push messages. By uninstalling most social media apps, I’m less likely to surf social media and form bad habits.

I reduced my contacts on social media to be roughly around Dunbar’s Number, which is a suggested cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships (150 people).

Whenever I find some information, I want to remember, I try to store it less often in digital form (I used to have 10000+ notes in Evernote), but instead, use analog more often, and create Sketchnotes of the basic concepts of an idea.

My calendar is nearly empty, I try to not fill it with appointments and live less planned.

And on multitasking: It simply doesn’t work for humans, this was proven in more than enough studies. Even the best multitaskers are slower while multitasking as if they would do the tasks in sequence. That’s why I try to single-task as often as possible. I keep my phones on the desk while watching TV and try to read less often while eating.

Conclusion

Minimalism is not a goal to reach, it’s a steady process, which you have to decide for from moment to moment. This is only possible if you are mindful and think about your relationship to material objects.

As JP Sears jokes: It’s not about being so poor, that you have the inability to have things. That’s poverty. It’s about being so rich, that you can afford to live like a poor person. Following the Minimalist philosophy will definitely be a benefit to your wealth. You will not be rich in things, but use your saved money to invest wisely, or spend it on intangible things, make experiences, follow your passions, and live a life worth remembering.

Recommended Videos, Articles, and Blogs

- Minimalism: A Documentary About The Important Things

- Less stuff, happier life

- Life is easy. Why do we make it so hard? | Jon Jandai | TEDxDoiSuthep

- TEDxO’Porto - Mark Boyle - The Moneyless Man

- Less stuff, more happiness | Graham Hill

- TEDxBoulder - Grant Blakeman - Minimalism - For a More Full Life

- A rich life with less stuff | The Minimalists | TEDxWhitefish

- TEDxAsheville - Adam Baker - Sell your crap. Pay your debt. Do what you love.

- The less you own, the more you have | Angela Horn | TEDxCapeTown

- What exactly is a ‘tiny house’? | Amy Henion | TEDxNortheasternU

- The Art of Enough

- The Minimalists

- Aesence/

- Becoming Minimalist

- Minimalissimo

- The Everyday Minimalist

- Minimlist Life

- 5 STYLE